A Rich Time: New York City in 1975

Drop Dead City, a documentary about municipal bonds and New York city's fiscal crisis, packs an emotional punch-- and knocks me out.

1.

Not that long ago, I was chatting with someone who works at my old high school, and a phrase floated by: “It’s great that you were here at such a rich time.”

The school’s name is not a secret, but I’d rather set it aside. The relevant details are that it’s located in New York City and I graduated in 1983.

“A rich time for the school, or for the city?” I replied.

She thought about it for a moment. “Both!”

The tone of the exchange was sunny, but the remark felt ambiguous. I thought about it for a while, and mentioned it to some friends, asking for their take. A particularly acerbic novelist I know put it under his bullshit detector and came back with the following result:

Translation: “Did you participate in the peak misogyny, rape and racism of this school, or just silently witness it?”

This made me laugh, and with that laughter I let go of the moment, or so I thought.

The line came back to me while watching a documentary, Drop Dead City, about New York City at the dawn of the “rich time” in question – when the drinks and the rent were cheap; CBGB’s was booking bands called The Ramones, Blondie, Television, and The Talking Heads; Soho was an industrial wasteland filled with abandoned lofts occupied by artists who sometimes used the buildings themselves as sculptural material; and something called Hip Hop was bubbling up in the Bronx, a musical style that had ancillary forms of dance and fashion and art, the latter using subways as canvas and the word “tagging,” in place of “painting.”

Several ironies about the phrase emerged as I watched Drop Dead City. The most obvious being that during New York’s long ago “rich time”, the city was broke.

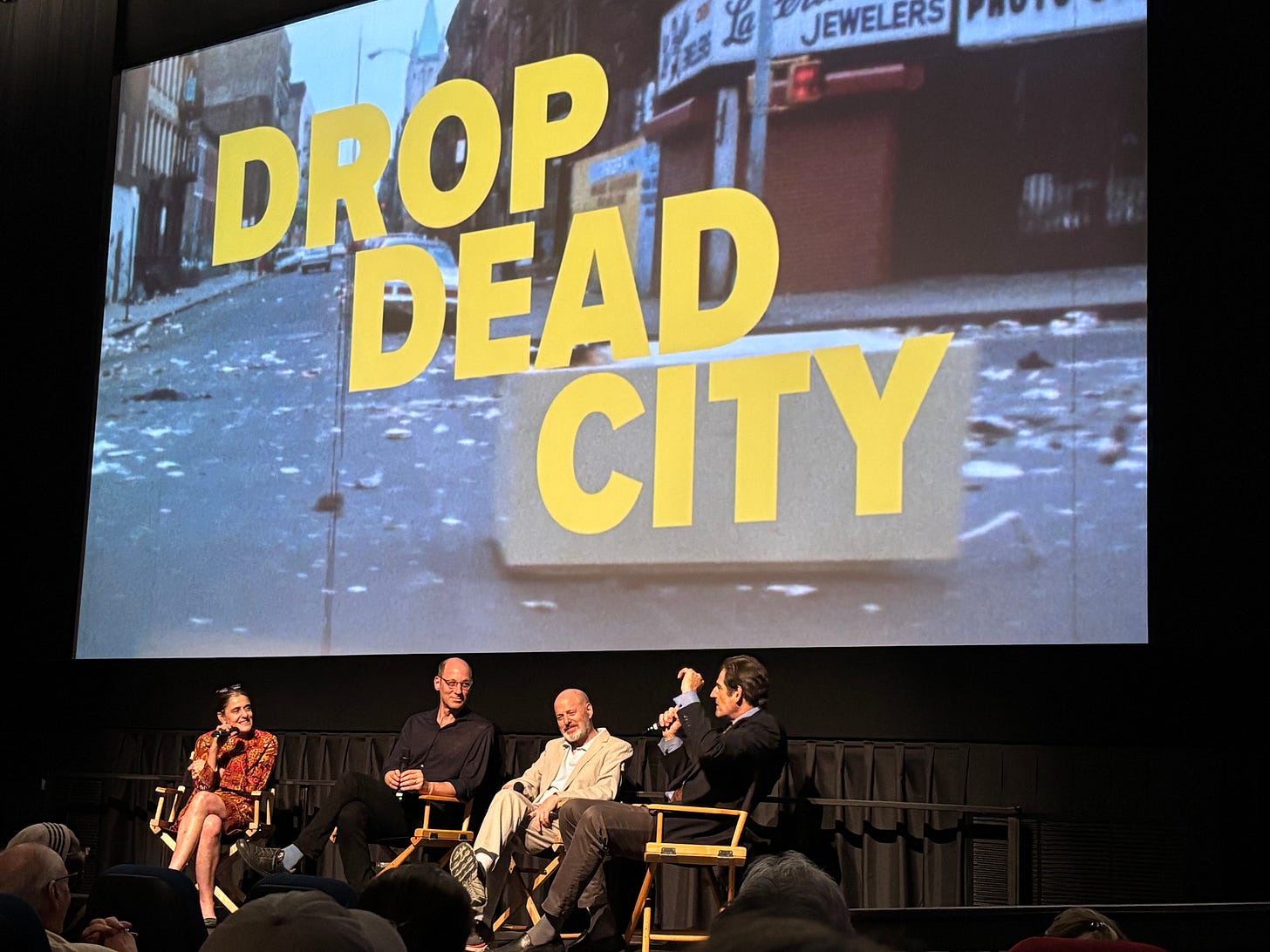

(L-R Bellafante, Yost, Rohatyn, Beller. Photo: Ed Park)

2.

I can’t write about movies. It’s like some blind spot, some cognitive disability. I lack the summarizing gene. For this reason, I was tempted to give up on trying to explain why the documentary film, Drop Dead City, had such a strong impact on me, and why I think it is so worth seeing. This in spite of having done a panel discussion with the filmmakers, moderated by Ginia Bellafante of the New York Times, after the Saturday night screening at the IFC. That night, I had found plenty of words. But now they escape me. Except for the part when I interrupted the filmmakers when one of them remarked that it wasn’t entirely clear who the villains of the movie are.

“It’s very clear who the villains are!” I barked into the mic. “Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney!”

These two men appear late in the movie, and if it weren’t for their names on the screen they would have been unrecognizable as the Dr. Strangelove-esque “Known Unknowns, and Unknown Unknowns” guy, and the other guy who was so scary that even after he shot a friend in the face with a shotgun meant to be aimed at a pheasant (and how do you confuse a man with a pheasant?), the friend didn’t file a complaint of any kind.

In 1975 Cheney and Rumsfeld were young, professorial looking conservatives who hated everything New York City stood for and/or everyone who lived there. They are pictured in richly technicolor, kodachrome photographs wearing ties and blazers, one of them smoking a pipe, both of them beaming at their boss, President Gerald Ford. It was these ghoulish guys who gave Ford the advice that, in a roundabout way, produced the New York’s second most famous1 tabloid headline: “Ford To City: Drop Dead.”

But I am getting ahead of myself.

3.

I would have bailed on the attempt to say something about Drop Dead City if it were not for a familiar shape that I recently spotted lying amidst the weeds and dirt in Riverside Park, a partly buried artifact from another world: The pull top ring of a can of beer. This innovation made its debut on a can of beer sometimes in the early 1970’s. For a while they were built into anything you could drink that came in a can.

And then, a decade and change later, they got phased out, a relic of a wasteful, polluting era. To see one lying on the ground in 2025 was to be transported nearly 50 years into the past. A span of time travel that mimics exactly the time travel of Drop Dead City. I picked the pull-top up out from the dirt that had 50 years worth dog excrement, auto exhaust, and pollution baked into it, and lifted it up to my face for closer examination. You would have thought I found a diamond or maybe the shroud of Turin. But no, it was a pull top of a can. I put it in my pocket and took it home.

Surely, I thought, this is a sign2.

4.

Drop Dead City is largely comprised of contemporary interviews expertly edited into B-roll footage of the city from that time. Since its protagonists include Mayor Abe Beame, Governor Hugh Carey, and various well known union leaders such as Albert Shanker, along with business titans whose names still ring a bell (Walter Wriston), and since the teetering fate of New York City was the object of global fascination, there is no shortage of contemporary footage from the era. We see phone booths, toll booths, rotary phones, subway turnstiles that work with tokens. A world that might once have seemed coldly mechanized now, in hindsight, seems bathed in a warm analog glow.

Above all, we see faces. They almost all fascinate, largely because of their imperfection. The range of facial expressions, the range of accents, and the range of clothing styles… but ‘range,’ is not the right word. I should say, the richness of the accents, clothes, cars, street life. Above all, the richness of the personalities. They are intense! There were moments watching the movie that I felt I was observing a species that lived 5000 years ago, not fity. But then I had to consider that the distance between now and 1975 is the same as the one that separated 1975 from 1925.

I stared transfixed by the dentistry and the comb overs, the wide wool ties and raincoats. I marvelled at the life they lead. The people on the screen live in an absence of which they are not aware. It looks so odd from the point of view of the sleek, minimal, mediated world in which we now live. I look at them (the world of my parent’s, and myself, I was there!) in a spirit similar, I would guess, to the way the citizens of 1975 looked back at the figures of 1925 making due without air conditioning, and whose refrigeration needs were met by huge blocks of ice delivered by the ice man— who cometh once or twice a week.

One of the curious things about the movie is that some of the most expert explanations of the financial machinations and stakes of the whole predicament are from the BBC, their expertise derived either from the lucidity that comes with distance or perhaps from having had some national experience of managing a giant enterprise that runs out of some combination of money and spirit.

By putting the words “money” and “spirit” besides one another, I am getting closer to what is profound about the film and the world it summons: a testimony to the ways these two properties are not the same thing, however one depends on the other.

5.

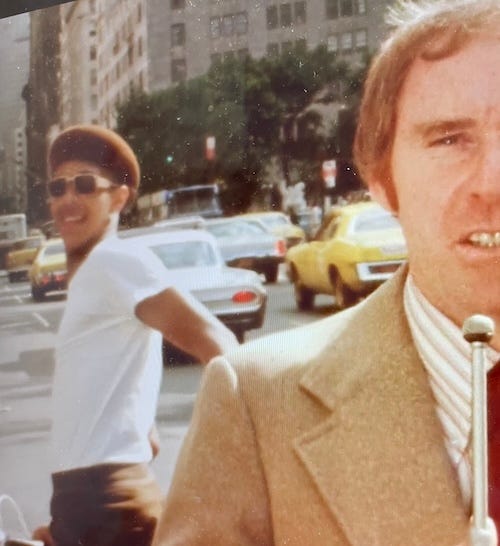

From the opening scene, in which a newscaster stands on 60th Street and Fifth Avenue3 facing North on a sunny day and attempts a spot that begins, “Surely, a significant portion of the Middle class fled New York City and moved to the suburbs…” I was filled with a nearly ecstatic sense of recognition.

The newscaster keeps having to start over from the top. First, a huge gust of steam escapes from a manhole cover and briefly engulfs him. As he prepares to start over we see a guy on a bike ride past. Fifth Avenue traffic streams behind him, heading South. You can see a bit of the Plaza Hotel. The cars and busses are so specific to that era. They are automotive Madelains. But so is his tie. So is his teeth. By which I mean, his teeth are fine, in fact since he is a newscaster they are very good but… but they are real. At times, I felt the whole movie could have been marketed with the title, 20th Century Teeth. The color, the shapes, the fillings of different hues and material flashing in the recesses of all those talking mouths. I haven’t thought so much about teeth since Martin Amis got his fixed.

But that is too glib; what I mean is that the voices and faces were not merely familiar from childhood, they were real in some way that went beyond personal nostalgia. Real in a way I found shocking. Even seeing the faces of newscasters such as Tom Brokaw, John Chancellor, and Walter Cronkite, faces meant for television, made me think this was another species. I learned in this movie that Hugh Carey entered the governor’s mansion as a widower with 12 children. There is some footage of him being a solo dad, cooking breakfast and brushing the hair of the youth before they march the door out to school. The guy was a politician for decades, in congress and then governor of the state of New York. The shot is staged! And yet it has something about the lives of that era that felt real.

6.

The ambivalence with which New York’s “Rich time” is regarded is a very strange thing, but understandable. On one hand, the Bronx was Burning, this town is shattered (“bite big the apple, don’t mind the maggots,” to quote Mick). On the other hand, everyone is there, on the streets and in the coffee shops and nightclubs, including John Lennon and Mick Jagger and Miles Davis, who was living in a brownstone with a pet goat. It’s possible Hannah Arendt saw this goat on the streets of the Upper West Side as she passed a newstands crammed with newspapers, one of which had the famous Daily News Headline from which the movie gets its name. She passed away about five weeks after it ran.

In some respects the city really does resemble, “a shithole,”4 especially after the fiscal crisis kicks in and they start laying off cops and firemen and sanitation workers. All of whom belong to unions.

And yet, it is a paradise of cheap rent and possibility. It’s like someone recalling the years after Rome burned and sighing, “Those were the days.”

The newscaster in that opening montage tries again and gets up a good head of steam, except behind him, edging into the frame, backing up, is the guy on a bike. A black guy with a beret who has a big smile on his face. It’s as though you could see a thought bubble above his head that read, “Hey! What up! I’m on TV!”

Timeless sentiments. But the model of the bike, and the funny, unfamiliar shape of the microphone being held by the TV news guy, and the cars cruising down 5th Ave into whose flow we see the beret wearing bike rider disappear on a subsequent take— it’s all so of a moment it took my breath away. As Charlayne Hunter-Gault, the Times journalist, put it, the city had “a coherence.” She was speaking of Harlem but I feel it applies more broadly.

I won’t make the mistake of confusing coherence with “unity” or even an amicable sort of civility. In fact these things were very much lacking. But nevertheless, the word rang out.

7.

It turns out there were some people I knew in the audience the night I spoke on the panel at the IFC, among them the writer Adalena Kavanagh. It turns out she was also moved by the film. I asked her why.

“The faces,” she wrote. “By using actual news and archival footage you saw so many real, lived-in faces. There’s this one scene where an older man and woman are being interviewed about investing in city bonds and his face is so cartoonish you almost couldn’t make it up! With the internet and an agreed upon set of beauty standards we have so much less variety.”

As it happens, my wife and I had laughed uproariously at this particular scene— a woman of a certain age is seated beside her husband on a park bench in front of what looks to me like a Mitchell-Lama (ie subsidized middle class housing) building.

“Ms. Kessler, I understand you hold some New York City Bonds,” asks the elegant interviewer. “What were you going to use the money for?”

The woman—Mrs. Kessler— speaks with great feeling about all the hard work they have put in which may go up in smoke if the city defaults on the bonds in which they have invested for their retirement. “Well! I do want it for the both of us for retirement purposes. Maybe we wouldn’t just have to live on the dregs…”

The camera cuts to a close up of her husband, smiling very broadly, an almost petrified kind of smile.

“Maybe,” Mrs. Kessler continues, “with our Municipal Bonds we would be able to live a little more comfortably.”

She speaks in an accent that now sounds like a strong New York accent, but at the time I suspect she would have been accused of putting on airs. When the camera pans to her husband sitting beside her you can almost see her rolling her eyes as the next question is directed at him.

Mr. Kessler’s smile remains utterly rigid and enormous, a mask. Asked if he has anything to add, he responds, “Not really, I think my wife has said everything.”

Then Mrs. Kessler, now out of the frame, says a line that I want to write a whole play around and cast Jerry Stiller and, in particular, Anne Meara as stars, as I can so imagine Ann uttering the following: “We certainly don’t have that many luxuries after all these years of living!”

Mr. Kessler holds the gaze of the interviewer and then seems to break the fourth wall and glances directly at the camera as if to say the viewer, ‘What? You think I am going contradict her? Are you, crazy?’ His face doesn’t move at all, the smile remains, everything is conveyed in the eyes, and maybe the teeth.

Adalena Kavanagh spoke of more than the faces, though. The movie is about politics, and she was able to articulate a response in the context of her current work in the city:

“The argument that the city was once run on liberal values (I’m not 100% sold on that argument) was interesting. I’ve been a teacher in NYC public schools since 2003. First as an English teacher, then as a high school librarian. I do wonder if the city’s paying fair wages to their unionized municipal staff up through the 1970s and then changing its attitude toward those same workers has anything to do with the fact that post 1970s the workforce became less white. When Bloomberg was in office he simply refused to negotiate the teacher’s contract so we went without raises for 8 years.

I liked the discussion about how the city once believed in lifting its people and how the film pointed to city work lifting people into the middle class, combined with free tuition at CUNY. Though now that there is this tremendous backlash against “DEI” and any work done to bring non-white people into the middle class, I can’t help think of free CUNY tuition, and the more welcoming attitude toward municipal workers as a sort of affirmative action for white immigrants and their children. Once white flight happened the incentives to keep those programs in place seem to have disappeared.”

As we watch the striking Sanitation workers, Teachers, Cops, and see the families of the laid off municipal workers, we can watch as they try to process what the drastic cuts and layoffs mean to their lives and to their city. Even in real time, there is a sense that this is a tipping point of some kind, a symbolic moment with concrete consequences. The solidarity and obstinacy of the union heads - the cops, the firemen, the sanitation, and the mother of them all, in some respects literally, the teachers - is so intense. In some respects, Drop Dead City is a real life superhero movie, except instead of Iron Man it’s Albert Shanker and the others guys trying to save their universe. It is in this context that Rumsfeld and Cheney appear; midwest conervatives who thought New York idealism - free college education for all its citizens! - was some kind of perversion of the American dream. These were the geniuses who pushed Ford to ditch Nelson Rockefeller (who the movie has to explain belonged to the now unfathomable category: “liberal republican”) in favor of Bob Dole as Ford’s running mate in 1976. They were tacking right to try and head off the conservative threat of Ronald Reagan.

Although it occurs fives years after the events in the film, I found myself thinking about that moment when Ronald Reagan fired the air traffic controllers. And of course one doesn’t have to look back further than yesterday’s papers to find allegories for cutting civil servant jobs and declaring them wasteful, profligate, unAmerican.

8.

I grew up in New York City and experienced those days in 1975 first hand. Not as a participant, exactly. I was too little to have any sense of the world in which I lived - to understand its population and politics, let alone finances - except in the ultra-vivid, unmoored from reality version available to children.

Partly for this reason, I am a big fan of the movies shot in New York City in the early and mid 1970’s. It’s an impressive list that includes The French Connection, Mean Streets, Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, Taxi Driver and The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3. Somewhat outside the chronological sweet spot of mid 1970’s New York, but deserving honorable mention: The Warriors, Saturday Night Fever, Kramer vs Kramer. All these are compelling movies in which the city itself, and its citizens, play an important role. But in terms of the degree to which a film transports you the New York City of that time, Drop Dead City eclipses them all.

Drop Dead City has been widely celebrated, but complaints have been registered—Michael Rohatyn, one of the two filmmakers, along with Peter Yost, is the son of one of the story’s main characters, Felix Rohatyn. Writing on the Rogerebert.com site, Jason Bailey said the failure to acknowledge this is a flaw, and makes the film seem like a piece of personal PR, a whitewash.

I strongly disagreed. There are many documentaries that make the autobiographical element explicit (Sherman’s March, My Architect, My Mother the Architect) but I think this movie benefits from leaving it out. Maybe I am naive, but whatever the film lost in objectivity it gained in a texture and soulfulness that infused the act of a son mourning a father. Felix Rohatyn appears only in archival footage; he was too ill to appear on camera and died while the film was in progress. The sense of grief and homage, of love in all its complicated reality, suffuses the film.

But maybe I am projecting.

My father died in 1975, in the spring that preceded the summer during which so much of the film takes place. I was nine.

“Most of us learn about New York City from the movies. Unless we’re raised there, we see things like Times Square on a screen before we do so in real life; it feels like so many of the images we associate in our minds with the Big Apple come from film.” This line is from a review of a book, Fun City Cinema, whose author is Jason Bailey.

If you were a kid in the city, this is reversed. You see the city in the movies and they reflect something back to you of the reality you experienced. But they are reflecting an absence. The Rich Time was rich because there was so much freedom and space, and within that, a great deal of fear and anxiety. You were constantly seeing things that were no longer there. I don’t mean that a store or a building that was a fixture of your life suddenly vanishes. There was plenty of that, too. Rather, I mean the feeling of growing up within a ruin. Of seeing spaces that are absent of something and even if you don’t know what was there, you feel it in some way. You are living with ghosts, spiritual, architectural, commercial. This is further echoed by the enormous emigre energy of that time, which gets me closer to something in Adalena’s remarks and in the footage itself, and also the Rumsfeld/Cheney loathing: how ethnic the city was, how foreign, specifically how Catholic and Jewish, categories that once blurred considerably in the imagination of Christian America.

But before I get all sentimental about the lost world of multi-ethnic New York, I want to point out that at many junctions in the movie I saw guys - men, white guys - who scared me. Or they reminded me of being scared. Some of the sanitation workers, I loved them to death on film, especially the guy in the budweiser fedora and the red T-shirt with an illustration of Mick Jagger, who was standing next to a guy whose hair was an Elvis pompadour, his accent straight out of Scorsese’s mobster movies. The accent is so real it’s hard to resist thinking it’s fake. But the footage of the city’s summertime streets strewn with trash is no joke. And oh man, that guy with the pompadour was hilarious. “I love picking up garbage,” he says while the guy in the Budweiser hat and the Mick T-shirt stands next him, nodding like a hype man. “That’s my money. What do you think I throw things in the street for? So I can have a job tomorrow! And I want Mayor Beame to know, Friday I’m coming to his house with my two kids. Make sure they feed ‘em.”

He is a riot, but the anger of these civil servants is real. Their accents, their teeth. Their fucking in your face anger. Real.

Which brings me all the way back to that inciting, thought provoking line, “You were here at such a rich time.”

I don’t think the remark was meant with hostility. It was a rich time. And a time that was the opposite of rich. The trash was spread around and so was the wealth. Such are the contradictions that are so beautifully spelled out in Drop Dead City. The people in that movie sensed they were on a precipice of some kind, and they were right.

I should certainly wait and let my thoughts marinate (like the pull-top of that can!) and develop before trying to write about Drop Dead City, but it is playing now - multiple times a day at the IFC Theater - and I want to get the word out while there is a chance for tickets to be sold. A film’s opening in New York has consequences for its future theatrical runs elsewhere. So please accept this provisional attempt.

**

Information about Drop Dead City screenings here.

The most famous headline appeared on the other tabloid and begins with the word “Headless.” If I am missing another candidate please let me know.

At home, I dropped it in a little glass bowl. I poured dish soap on it, and then boiling water. I did this several times. I tried to polish it, at which point the little tongue of the pull top broke off from the ring. For a moment I felt the conservator’s panic: I had ruined this tiny, valuable artifact. The whole time I bathed the thing I was thinking of the opening scene of the Bad News Bears, the one where Walter Matthau rolls up in his convertible beater Cadillac, gets a beer from the cooler in back, and, to the accompaniment of the “shush-shush” of sprinklers watering the perfect lawns of a Los Angeles baseball diamond, pulls the top off a can of beer. He then sends that little piece of tin over the side of the car.

I saw that movie ten times when it came out in theaters in 1976. I have written about this weird obsession with the Bad News Bears (and also Breaking Away) in my next book. I have gone back and rewound - or hit the back arrow on the computer - on that moment many times. You can hear the plink of that top hit the pavement, a tiny piece of litter added to the gigantic towering pile of garbage that the world seemed to be turning into, with only a solitary tear of an American Indian to beat back the tide. (The Indian turned out to be an Italian from Louisiana.)

I couldn’t get that fifty year old pull-tab clean. So I left it marinating in the little glass bowl of dish soap and boiling water and then, when it cooled, I covered it within Saran-wrap and hid it in the refrigerator.

A few steps from the Metropolitan Club, on the North side of the street, which faces The Harmonie Club on the South side of the street, built by the old German Jews after the WASPS at the Metropolitan Club wouldn’t let them join.

Of course, to even jokingly call any place “a shithole,” is to quote one of the ugliest creatures birthed by this very shithole, and by this very time—the man who is now the president of the United States of America. This fact that is not part of the movie but in some ways informs the experience of watching it.

Would I choose the art, music, movies, and books created in NYC in the 1970s over the art created in NYC now? Absolutely. No question. There's no debate even possible. There is no whisper of an argument for now.

Wonderful piece, which wanders in such an intriguing way and ends as good narratives often do, back where it began. And to join the comments’ conversation I just now walked out of the documentary seeped in 70s New York and emerged on 6th avenue and 4th street at 6 pm with the diverse Steinberg New York multitudes surging in and out of the subway and skipping across the avenue where on the other side pedestrians gawked at a fierce basketball game and dudes hung out by their music box. New York has changed but luckily much of its dynamism and energy is still there.